Reflections on Harry Somers

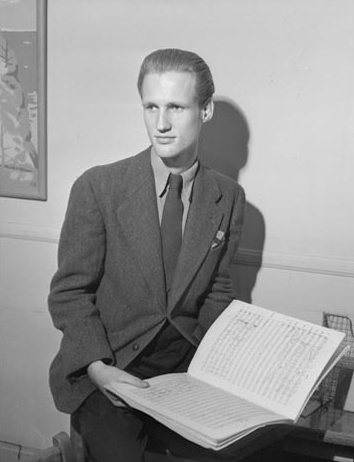

Harry Somers came to formal music study relatively late, with piano lessons at age 14, but completed ten years’ worth of piano study in just three years. From the start, his piano studies were complemented by a creative impulse, one that would be nourished and developed through training with John Weinzweig, the leading composition teacher in Toronto during the postwar era. Somers put aside his early aspirations to a career as a concert pianist to devote himself to full-time creative work, and in 1949 he moved to Paris to study with the French composer Darius Milhaud for a year.

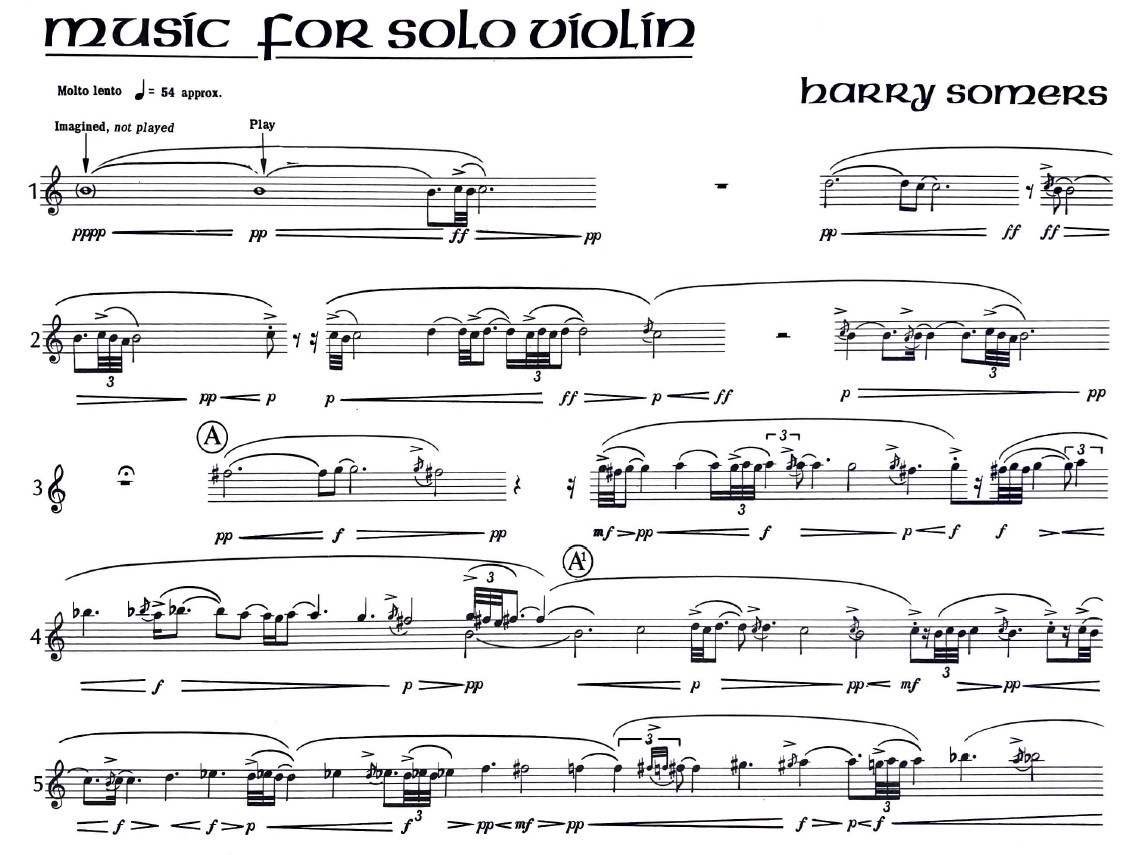

By his mid-20s, Somers was composing mature works that are valued as among the finest Canadian music from that period. He developed an effective, distinctive musical language that drew upon a contemporary compositional idiom but framed it within techniques and structures of the eighteenth century. North Country for string orchestra (1948) marked the end of his apprenticeship with Weinzweig and his first maturity as a composer. The signal achievement of Somers’s Paris sojourn was his String Quartet No. 2 (1950), “one of the most impressive works of Somers’ entire career” according to the composer’s biographer Brian Cherney (Harry Somers, 1975, p. 48). This work ushered in an enormously productive period in Somers’s life, with dozens of works flowing from his pen in the 1950s, many for his own instrument, the piano, often combining twelve-tone techniques with fugue.

Each major new work by Somers received multiple performances by major soloists and ensembles, was published and recorded, and was broadcast on the CBC Radio network. He also became a persuasive advocate for Canadian contemporary classical music, lending his mellifluous and well-modulated speaking voice to regular work as a freelance broadcaster on CBC Radio. Handsome, personable, and hardworking, he was a hugely talented and productive creative artist.

After another year spent in Paris (1960–61), a series of significant commissions followed in the 1960s. An increasing engagement with music for voice culminated in the Centennial opera Louis Riel. The defining moment of his career was the celebrated premiere of this full-length opera by the Canadian Opera Company in 1967. Although he was never to replicate the success of that Centennial commission, he continued to grow his catalogue with major works for a wide variety of performing forces.

Somers spent two years (1969–71) in Rome, writing the virtuosic Voiceplay (1971, for solo voice and accompanist) for Cathy Berberian. From the 1970s to his death, Somers enjoyed a reputation as one of Canada’s finest composers, adding steadily to his significant list of major compositions and honours. He was the first composer to be made a Companion of the Order of Canada (in 1971) and received honorary doctorates from three universities (1975–76). The biography by Brian Cherney was published by University of Toronto Press in 1975 to mark the composer’s 50th birthday. The Canadian Opera Company premiere of Somers’s last opera, Mario and the Magician (based on the novella by Thomas Mann), was given in Toronto in 1992. In 1995, his 70th birthday was marked by tribute concerts. The Third Piano Concerto from 1996 was his last major work; a few other smaller works ensued but his career was cut short at age 73 in 1999 by cancer.

Aside from an hour-long audio documentary completed seven years after Somers’s death (Cornfield 2006), there has been no major account of Somers’s career since the Cherney biography in 1975. This leaves the last 24 years of Somers’s life largely unaccounted for, a lamentable situation for one of Canada’s major creative artists. The recent publication of Somers’s correspondence with Norma Beecroft (Cherney 2024) is another testament to the importance of Somers’s career and his place in the history of Canadian classical music.

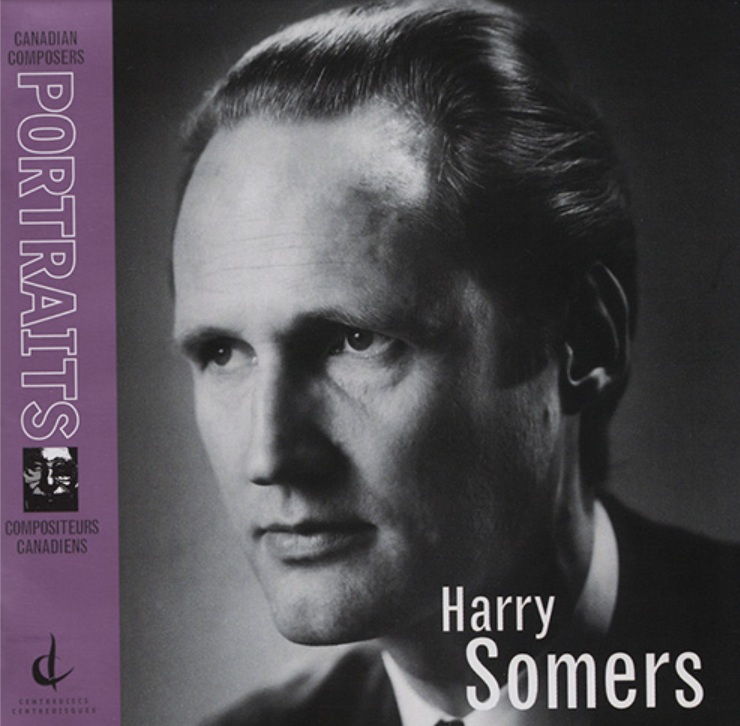

After his death, many of his major works were issued on a series of recordings titled “A Window on Somers” (see below). The Canadian Opera Company’s Sesquicentennial production of the opera Louis Riel in 2017 has been the focus of extensive critical commentary. Discussions have largely centred on Indigenous objections to the use by Somers of material from a Nisga’a song (recorded by Marius Barbeau in 1927 and transcribed by Ernest MacMillan) as the basis for “Kuyas,” a lullaby sung by Riel’s wife Marguerite at the start of Act 3. In response to these concerns, the Métis composer Ian Cusson was commissioned in 2019 to compose “Dodo mon tout petit,” a replacement aria for “Kuyas,” with the agreement of the estates of Somers and the librettist Mavor Moore. Whether this replacement aria successfully addresses Indigenous concerns about the work, or simply papers them over, remains an unanswered question. The wider issue of the cultural appropriation involved in having settler Canadians tell the story of the Métis leader Louis Riel in a Eurocentric art form raises thorny questions that are still being debated by Indigenous, Métis, and settler commentators. Visit the Resources page for a list of written commentaries on Somers’ life and career, and a discography of some of the major recordings of his music.

The complicated process by which a composer’s legacy is shaped and sustained after their death is not well understood. In the field of contemporary classical music, much depends on the active efforts of the composer during their lifetime to promote their music through cultivating personal contacts, building relationships with performers, appearing in public to speak about their work, and so on. Upon their death, the responsibility for these efforts falls to others, and inevitably interest declines when there is no new content being created. While Louis Riel is just one work in an extensive catalogue of compositions by Somers, it has played an outsized role in his posthumous legacy, as the controversial reception of the 2017 production demonstrates. Now that the dust from that reception history has begun to settle, it is an appropriate time to weigh the consequences of this debate on the legacy not just of that one opera, but of Somers’s career in general.

Join us at the University of Toronto Faculty of Music on September 27th as we take stock of a great Canadian composer on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of his birth.

A Window on Somers series: all from the Centrediscs label

- Singing Somers Theatre CMCCD 6901 (2001)

- Songs from the Heart of Somers CMCCD 7001 (2001)

- The Glorious Sounds of Somers CMCCD 7101 (2001)

- Somers Strings CMCCD 7401 (2001)

- Somers String Quartets CMCCD 7501 (2001)

- Serinette CMCCD 76/7701 (2001)

- A Midwinter Night’s Dream CMCCD 12306 (2006)

- The Fool / The Death of Enkidu CMCCD 14209 (2009)

- Piano Works CMCCD 14509 (2009)

- Chura-Churum / The Merman of Orford CMCCD 15309 (2009)

- Live from Toronto: Harry Somers CMCCD 15911 (2011)

- Louis Riel CMCDVD 16711 (2011)